Faced with a pandemic, growing inequality, and widespread dissatisfaction, the Kremlin has launched a series of measures aimed at consolidating Russia’s authoritarian political system. Will they work? In an article for the Carnegie Moscow Center political scientist Andrei Kolesnikov and sociologist Denis Volkov take stock of the turbulent year 2020 and note that Putin's majority has become unstable.

Poster for the popular vote for the constitutional amendments, saying 'Stability and development'

Poster for the popular vote for the constitutional amendments, saying 'Stability and development'

by Andrei Kolesnikov and Denis Volkov

The Kremlin’s top political priority in 2020 was not the fight against the novel coronavirus, but rather the engineering of heavy-handed changes to Russia’s 1990s-era constitution. By disposing of inconvenient presidential term limits that could have forced Vladimir Putin to step down in 2024, the national vote held in July 2020 was supposed to reduce the risk of Putin increasingly being seen as a lame duck ahead of 2024 and to short-circuit any behind-the-scenes maneuvering to succeed him.

Yet in reality, rather than solving the difficult issue of succession, the Kremlin’s maneuvers have only postponed it. While the path is now clear for Putin to serve until 2030 or even 2036, the fate of Russia is still entirely in his hands. Indeed, Putin could end up feeling forced to call early presidential elections or he might even step down in 2024, surprising everyone once again.

Stagnation

Not everything in Russia, of course, will be shaped by Putin’s decision on when or how he leaves the scene. Challenges abound, and the Russian political regime is facing a growing number of them. One, common to all nations, is the COVID-19 pandemic, which has hit Russia very hard. By late autumn 2020, Russia had the fourth-highest number of people infected. The economic consequences of the pandemic have compounded the impact of a decade-long period of near-zero growth and stagnation. Against a backdrop of growing social inequality, it is no surprise that public frustration and dissatisfaction are growing. This state of affairs is readily apparent in places as different and far apart as Khabarovsk in the Far East and Kushtau in Bashkortostan.

On top of this, the confrontation with the United States continues. There is no expectation of any letup under President-elect Joe Biden. Relations with the European Union have deteriorated to a record low. The chronic unrest in neighboring Belarus has sent a warning to Moscow of possible risks for Russia itself over how the public may react to a long-standing ruler reluctant to leave power. No wonder even the prospect of political transition to a post-Putin era provokes fears inside the Kremlin of intra-elite rivalries and potential destabilization.

A new prime minister, Mikhail Mishustin (right), on his way to be introduced to the State Duma. Picture duma.gov.ru

A new prime minister, Mikhail Mishustin (right), on his way to be introduced to the State Duma. Picture duma.gov.ru

Faced with these negative factors, the Kremlin launched a series of measures designed to tighten up the political regime. These include the government reshuffle in January 2020, which was accomplished by means of a secret operation. The Kremlin-backed series of constitutional changes also restored the supremacy of Russia’s national law over international decisions and made it a criminal offense to question the country’s territorial integrity. In addition, the regime is testing new election procedures that help boost support for the Kremlin-backed ruling party. It has toughened the rules barring public protests, and accelerated a crackdown on politically or socially engaged groups and individuals who get foreign funding. All of these initiatives are aimed at further consolidating Russia’s authoritarian political system. Will they work?

An unstable majority

The mainstay of the Russian system and of Putin’s regime of personal rule has been the steady level of support for the president among a solid majority of Russian people. Popular support for the president spiked at over 80 percent in the wake of Russia’s seizure of Crimea in early 2014. Over time it slid back to the low 60s, where it stabilized. This solid popular support base is known as the Putin majority. Now signs are appearing that this majority may be crumbling a little at the edges, for several reasons.

The Kremlin traditionally relies on the population remaining quiescent. Under this social contract, ordinary people stay out of the affairs of the state in exchange for the elites providing them with basic physical and social security guarantees, a sense of national greatness, and a pledge not to interfere too intrusively in their own affairs. This worked well when the economy was growing, and most people, focused on their own day-to-day needs, were generally content with the basic services provided by the state. Today such state support is falling short in an environment shaped by economic stagnation and rising expectations.

In the post-Crimea period, many ordinary people’s hopes for achieving greater national unity and social solidarity, disciplining the corrupt elites, cleansing the bureaucracy in favor of meritocracy and efficiency, engineering economic revival, and raising living standards have been thoroughly dispelled. While the July 2020 vote showed strong support for the amendments to the constitution, actual popular attitudes are more complex. Just one month prior to the vote, polls demonstrated that public opinion was split: only 44 percent of those polled backed the amendments versus 32 percent who opposed them. However, among those who intended to vote, supporters of the amendments outnumbered those who opposed them by a margin of 55 to 25 percent.

Mobilizing support, demobilizing opposition

The Kremlin achieved its desired result by successfully mobilizing its supporters through unprecedented levels of campaigning and changes to the mechanics of how elections are held. For example, the authorities extended the voting period from one day to one week and made it much easier to vote. They created makeshift polling locations across the country, including sites based in car trunks and on tree stumps. There were also credible reports of coerced voting, illegal campaigning by the local authorities, and interference in the work of outside election monitors.

Make shift polling station during the popular vote on the constitutional amendments. Picture copyright free

Make shift polling station during the popular vote on the constitutional amendments. Picture copyright free

While the would-be supporters of the amendments were thus mobilized, any opposition to them was demobilized due to the fact that all the amendments—including noncontroversial and even popular social, ecological, and cultural adjustments—were voted on as a package. In that situation, opposition political groups failed to mount a campaign that would prevail over fatalism and general passivity among even the most disgruntled Russians. Many of them became convinced that their actions would not have any impact on the ultimate outcome of the vote.

Sociological data allow us to conclude that the so-called Putin majority has demonstrated new features that make it less impenetrable. These features include new aspects of electoral behavior: voting on autopilot and voting as a ritual. This behavior no longer matches the real popular mood, and does not reflect the dissatisfaction with the quality of state-provided services, and with the socioeconomic situation in general. As the constitutional vote suggests, the Putin majority can still be mobilized on an ad hoc basis, during election campaigns—mostly at the federal level—but otherwise it is not sustainable.

Protests in Khabarovsk

This conclusion is confirmed by the protests in Khabarovsk, a major city of 600,000 in Russia’s Far East. Although 62.3 percent of voters in Khabarovsk approved of the Kremlin-proposed amendments, including abolishing presidential term limits for Putin, huge numbers took to the streets just a few weeks later. They were furious over Moscow’s decision to arrest the region’s popular governor Sergei Furgal on criminal charges. The mass protests lasted for many weeks, with some demonstrators chanting anti-Putin slogans. While Putin the president remains, in the eyes of 'his' majority, the unquestioned symbol of national unity, Putin the politician—i.e., the specific actions that he takes and the officials whom he appoints—is not perceived as infallible.

Demonstration for the release of governor Furgal (image copyright free)

Demonstration for the release of governor Furgal (image copyright free)

Khabarovsk also reveals something else: the slow but perceptible rise of Russian civil society. Putin’s majority mostly makes itself visible at the ballot box. Absent such mobilization, according to Lev Gudkov, director of the Levada Center, only 30–35 percent of the public backs Putin, with roughly half of them being firm supporters. The regime’s opponents make up 10–15 percent of the population. The rest—50–55 percent of the population—are essentially politically indifferent, says Gudkov. The slow contraction of the pro-regime majority is accompanied by the rise of social activism. This represents another challenge to the Kremlin.

Does civil society matter?

Russia’s civil society is developing a new agenda. Its main goal is upholding various rights that are being violated, including environmental, social, and electoral rights. This is not an organized movement in support of human rights, nor is it political, but it is a challenge to the authorities, nonetheless. The Kremlin has developed tactics for dealing with urban political protests, and is constantly updating its toolkit for repression. Recently introduced Duma legislation that would outlaw even street protests by solo picketers is a case in point. In addition, the Duma has recently expanded the notion of a 'foreign agent' to include individuals alongside organizations. The idea is to expand the ability to identify, isolate, discredit, and penalize any individuals who actively oppose the existing political regime, and put them under severe pressure.

Dealing with civil society as a whole is more difficult. The Kremlin’s strategy is to encourage the conformist elements within society and pull more passive members of the public over to its own side. The authorities are even adopting parts of civil society’s agenda as their own. Thus, Putin personally intervened on behalf of environmental protesters in Bashkortostan who opposed a mining project at Kushtau Mountain. The project was being developed by a private company with close ties to the local authorities, and the protest was met with brutal police repression. Putin, however, managed to link the environmental protest to widespread mistrust of big private business. He argued that had the company remained state-owned, no one would have pursued such a problematic project.

Thus, President Putin solved several problems simultaneously. He reaffirmed his image as the top arbiter, he stopped the protest using peaceful means, and he showed the conservative part of society his commitment to state interference in economic processes. In doing so, Putin de facto embraced the agenda of conservative opponents to the current status quo. He chose to make concessions on a relatively minor issue and hinted at the possibility of nationalizing private companies. Focus groups conducted by Carnegie Moscow Center and the Levada Center indicate that such views represent a key component of the future political agenda for conservative-minded Russians. Putin will need to take into account the presence of those social strata that are more conservative than himself.

The president is used to balancing the interests of various social groups and arbitrating disputes between them, and was able to deal with the Kushtau case. Other protests may be more challenging, even for him. What happened in Khabarovsk over the dismissal and arrest of Sergei Furgal, a political outsider tied to Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s Liberal Democratic Party who had defeated a candidate backed by the ruling United Russia party, is a case in point.

Indignation and dissatisfaction

Furgal was accused of having ordered, years ago, the murders of his business rivals. He was arrested and taken to Moscow. However, many residents of the region viewed Furgal as an effective and even caring governor. His sudden arrest led many to believe that the authorities had stolen their choice: a rare occurrence of such indignation in Russia, where governors are often replaced and frequently arrested and convicted of bribery and economic crimes. The case of the Khabarovsk governor was different: it led to mass protests that lasted for months. These protests transformed a routine case of a senior official being replaced and arrested on criminal charges into a national story that even federal state-run TV channels could not ignore.

The protests were not political, however, and nor were they led by opposition leaders. Rather, they were driven by Khabarovsk residents’ perception that their dignity and electoral rights had been violated, just like in Bashkortostan, where the encroachment on Kushtau Mountain, a natural treasure of the Bashkir people, was seen as a threat to people’s ethnic identity and human dignity.

Projected area for landfill in Shiyes in the Arkhangelsk region was abandoned after protests. Picture ejatlas.org

Projected area for landfill in Shiyes in the Arkhangelsk region was abandoned after protests. Picture ejatlas.org

As in other cases, such as the 2019 protests in Shiyes in the Arkhangelsk region, Yekaterinburg in the Urals, Ingushetia in the North Caucasus, and Moscow itself, the manifestations of civil society awakening across the country are not usually prompted by a political trigger, though political overtones sometimes emerge during the course of events. A cross-section of participants in the demonstrations also revealed a social base that was considerably broader than the urban middle class that has been the backbone of protests in Moscow and other major cities since late 2011.

Thus, the protests in Khabarovsk highlighted popular demand for new faces in politics. Whatever his past, Furgal proved to be a skilled politician who consolidated his popularity by cutting privileges for the local bureaucracy and providing free meals in local schools. He also publicized his policies through local television and social networks. When his broadly televised arrest turned the national spotlight on him, the story of his governorship was well documented online for anyone interested in it. By taking to the streets of Khabarovsk, local people were defending their elected and popular leader from interference from faraway Moscow, thus challenging the federal government and President Putin himself.

Public sympathy for these types of protests is relatively high, reflecting the currently elevated level of dissatisfaction with the federal government. In an August 2020 Levada Center national poll, 47 percent of respondents said they had a positive view of the Khabarovsk protests, while 32 percent believed that “the federal government gets rid of politicians who enjoy broad popular support.” But in spite of all the sympathy, there were hardly any rallies in support of Khabarovsk across the country, maybe because most Russians believed that it was hopeless. Roughly half of Russians surveyed in a national poll said they were sure that the government would not make any concessions to civil society on the Furgal issue.

Ruthless to opponents, concessions to voters

In this sense, the 2020 Khabarovsk case is similar to the Moscow protests of 2019, rather than other recent regional protests. The Kremlin remains ruthless and intransigent on what it considers to be fundamental issues, such as Furgal’s arrest; the removal of opposition candidates from Moscow City Duma elections and gubernatorial elections in 2019–2020; and the criminal prosecution and deprivation of electoral rights of members of the opposition (Alexei Navalny’s supporters and Open Russia activists). On the other hand, the Kremlin is prepared to consider making concessions when disputes do not pose a direct challenge to the regime, and when doing so could reduce the level of overall dissatisfaction, demobilize critics, and defuse the situation without a significant loss of face.

Newspapers with identical front page campaigning for release investigating journalist: 'We are Ivan Golunov'. Picture free of copyright

Newspapers with identical front page campaigning for release investigating journalist: 'We are Ivan Golunov'. Picture free of copyright

Putin’s lower approval ratings in the wake of the unpopular 2018 move to raise the retirement age and growing levels of popular dissatisfaction with officials are fostering an environment in which ordinary people are organizing themselves more frequently and managing to obtain at least some concessions from the authorities. That is what happened in Yekaterinburg when civic protests stopped the construction of a new church in a popular park area; and when the authorities released the investigative journalist Ivan Golunov, who had been arrested on trumped-up drug charges in 2019. This was also the case in Shiyes, where an unpopular landfill project for burying waste transported from Moscow was stopped.

Thus, in recent years the Kremlin has been ruthless with regard to political opponents who are deemed dangerous, while at the same time showing a degree of flexibility when dealing with civil society protests. In 2020, however, it faced a challenge of a different kind right next door, but with clear implications for Russia itself.

Upheaval in Belarus

In August 2020, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, in power since 1994, ran into trouble after proclaiming himself the winner of a blatantly fraudulent election. That led to mass demonstrations that have been held in the country on a weekly basis ever since. Moscow has long been unhappy with Lukashenko. There is no affection for his lack of enthusiasm for closer integration with Russia coupled with permanent demands for subsidies, his mistreatment of Russian business interests inside Belarus, or his recent incremental drift away from Moscow and toward closer ties with the European Union and the United States.

Still, Moscow was deeply worried about the prospect of a Ukrainian Maidan-style uprising in Belarus with support from neighboring EU/NATO member states such as Poland and Lithuania. Putin hinted broadly at his willingness to use force to preserve the status quo in Minsk. Yet he also surely recognized that any attempt to intervene militarily in the standoff between the Lukashenko regime and Belarus’s newly awakened civil society risked alienating the people of Belarus and replaying the course of events in Ukraine: precisely what Russia was seeking to avoid in the first place. And any successor to Lukashenko imposed by Moscow would surely be seen by Belarusian civil society as an occupier. Against that backdrop, the Kremlin opted for a far less risky and less costly approach. It ramped up diplomatic and political support for Lukashenko, who had lost his ability to play the West and Russia off of each other.

Lukashenko in the eyes of Russians

Very close ties between Belarus and Russia inevitably raise the question of the implications of the Belarusian developments for Russia. Interestingly, Russian public opinion about the crisis has been rather heterogenous. The more liberal segments of Russian society, as well as a significant proportion of young Russians, see Belarus’s aborted velvet revolution as an attractive example of peaceful and disciplined protest worthy of imitation. The triggers for the protests in Belarus and Khabarovsk were different, but what they have in common is that they are nonviolent civil society actions. (In Belarus, of course, there is also a political opposition element now mostly based abroad, as well as the pressure of Western sanctions on Lukashenko.)

The Lukashenkon regime enjoys suprisingly strong support among elderly Russians. Picture president Belarus

The Lukashenkon regime enjoys suprisingly strong support among elderly Russians. Picture president Belarus

At the same time, the Lukashenko regime enjoys surprisingly strong support from a significant proportion of Russians—above all among the older generation. In their eyes, the regime is a model to emulate, and Lukashenko himself has advantages over Putin. According to a survey conducted by the authors in 2019, the two countries that were named most frequently as attractive models for Russia’s future development were China and Belarus. These segments of the Russian public see the Belarusian protests as a threat to law and order and as yet another example of foreign interference in and outside manipulation of the domestic affairs of a friendly neighboring country.

Many Russians have followed the events in Belarus, but only very generally. Research by the Levada Center showed that relatively few people were able to talk at length about the motivations that guide the protesters. This lack of keen interest helps contribute to a fairly strong feeling in favor of Lukashenko remaining in power: better the devil you know. Few Russians surveyed expect the protests to force Lukashenko to step down. A majority hopes that the ongoing crisis will be solved at the negotiating table, but they expect the Belarusian government to make only small concessions. A third of Russians do not rule out the use of force in Belarus by the Kremlin. While there is some support for the protesters, few believe they will succeed.

Reactions to the Belarus crisis reveal what Russians think about the state of affairs in their own country, and some parallels can be easily drawn between Minsk and the protests in Khabarovsk and Moscow. True, street protests can help to attract the attention of the authorities to unresolved challenges or to get local problems addressed. By contrast, labor actions and general strikes— which have been attempted without much success in Belarus—are not seen as a proper tool to address fundamental issues like who gets to rule the country.

Still, events in Belarus have prompted both opposition activists and the authorities to ponder whether a Belarusian scenario might play out in Russia in the context of the 2024 presidential election. For the time being, the Russian authorities are watching how the system of total repression of civil society works. As for Russian civil society, it is watching what results resistance can produce. The Belarus crisis could be a testing ground for what might happen in Russia in a few years’ time.

The Navalny factor

The attempted assassination of the opposition politician Alexei Navalny in August 2020 was a milestone in Russia’s foreign relations, primarily with the European Union. Given Western perceptions of Navalny’s political significance, the attack led to a visible hardening of European attitudes and policies toward Russia, above all in Germany, where Navalny was flown for treatment. Within Russia, however, the attack did not have a transformative impact on the attitudes of Russians toward Navalny. This is striking, because for the past five or six years, he has been consistently ranked among the ten most trusted politicians in Russia.

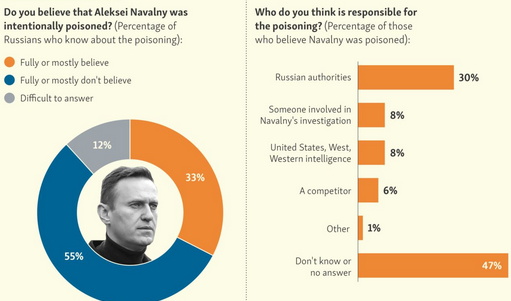

Within Russia the attack on Navalny did not have a tranformative impact on the attitude of Russians. Graphic rferl.org

Of course, Navalny’s comparatively high ratings are largely a product of the public’s relatively free access to social networks and independent media resources, including Navalny’s extremely popular YouTube channels. By contrast, the much larger viewership of Russian state-controlled TV continues to express a generally negative attitude toward Navalny. According to a Levada Center poll conducted in September 2020, 45 percent of respondents 'had no particular reaction' to the attempted assassination of Russia’s most recognizable and uncompromising opposition politician. Only 18 percent of respondents were 'paying close attention' to the story, while 59 percent 'had heard something about it.'

Such attitudes can be explained by the fatigue and passivity that are characteristic of the bulk of Russia’s population. Attacks on opposition leaders do not trigger a sense of crisis. Rather, the public is becoming inured to such events. Thus, there was only a low-key reaction in fall 2020 to the self-immolation of Nizhny Novgorod political activist and journalist Irina Slavina. High-profile cases such as the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 over Ukraine’s Donbas region in 2014 and the poisoning of the former Russian intelligence officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter in the UK in 2018 also failed to elicit strong public reaction in Russia. Instead, most people simply accept the versions of events advanced by the Russian authorities.

Indifference

This phenomenon could be described as informed indifference: an unwillingness to pay attention to bad news and a desire to block out self-reflection about extraordinary, disturbing events. According to the same Levada Center polling, 55 percent of Russians do not trust reports that Navalny was deliberately poisoned, and 47 percent find it difficult to say who may have been behind the crime. At the same time, 30 percent indicated that they suspected the 'current regime' was responsible, while 8 percent embraced senior Russian officials’ assertions that it was carried out by the United States, the West, and Western secret services.

The absence of solidarity within the opposition after the attack on Navalny likely reflects the existing rifts among various Russian opposition groups. Incidentally, that was also evident during the campaign ahead of the constitutional vote. There is a degree of jealousy toward Navalny outside the circle of his active supporters. Moreover, Navalny’s sudden incapacitation as the unquestioned leader of his group has had a disorganizing effect on his supporters, who felt disoriented without clear directions coming from him. Of course, restrictions on mass rallies due to the pandemic—alongside the tightening of the rules governing them—likely discouraged many of Navalny’s supporters from demonstrating their solidarity.

The authorities, for their part, have used Navalny’s stay in Germany to discredit him as a foreign agent. If and when Navalny decides to return to Russia, the Kremlin will face a dilemma: allow him in, and treat him as public enemy number one, or try to deter him from coming back by reopening or initiating lawsuits against him, and ultimately putting him in prison. So far, all the signs point to the latter course. Keeping Navalny out of the country may be the one good outcome for the Kremlin from the entire affair.

What next?

Removing the limitation on presidential terms for Putin has failed to solve the Kremlin’s political problems. The spike in the COVID-19 pandemic in October-November 2020 was much more severe than anything Russia had experienced since the virus first arrived in the country. The second- and third-order consequences of the disruptions and dislocations wrought by the pandemic may be dramatic. The cabinet that Putin installed in January 2020 to spur on the economy has had to focus on public health issues. Putin’s majority has proven to be conditional rather than absolute. Public disgruntlement and discontent are widespread, and Joe Biden’s victory in the U.S. presidential election promises a tougher and more coordinated Western approach to Russia.

The 2024 election is still a few years away, but 2021 will see Russia’s second most important vote: for the State Duma. Even with new techniques in hand and Navalny out of the country, this will not be a walk in the park for the Kremlin. During the pandemic, Putin was loathe to simply hand out money to the population. At the same time, he certainly understands how important social issues are for ordinary Russians. As Russia’s economic model has stalled in recent years, it has become increasingly clear that growing numbers of Russians have become more dependent on the state. To get their votes, the state will have to demonstrate that it is willing to provide a modicum of social support.

The vast majority of the Russian population remains paternalist and conservative. The authorities will play on that and present voters with a wide array of domestic and external threats that the state is supposedly protecting them from. This is likely to resonate with the public. Most Russians continue to place their trust in three key institutions above all others: the army, the president, and the FSB (the Federal Security Service) and other security services, in that order. By contrast, democratic institutions such as the State Duma, political parties, and the media, which have been essentially hollowed out in recent years, are largely discredited. They enjoy very low levels of trust among average Russians.

Billboard at the eve of the popular vote for the constitutional amensments saying 'Putin for ever'. Picture copyright free.

Billboard at the eve of the popular vote for the constitutional amensments saying 'Putin for ever'. Picture copyright free.

The Kremlin wants to take no chances, it seems. The recently passed law on the absolute immunity of former Russian presidents demonstrates that the Russian authorities are seriously preparing for a variety of scenarios: the sudden illness and incapacitation of Vladimir Putin; a sharp decline in his popularity; and the preservation of Putin as president for a very long time. The adoption of this legislation does not mean that Putin is going to leave soon. Rather, it is just an additional safety net for the possible extension of his presidency to 2036. The 2021 parliamentary elections will be held on time, and the 2024 presidential election—barring a force majeure—will run as scheduled too, most likely with Putin’s participation.

It is, of course, impossible to predict whether the 2024 election will be held amid an atmosphere of calm. This is why in the Belarusian scenario that is still unfolding, the Russian authorities see a vision of their possible future and demonstration of various models of behavior in the event of unrest by elements of Russian civil society. The Kremlin believes that it must be ready to uphold Putin’s continued rule. Yet at the same time, it must also be able to deal with dissatisfaction with his long reign, and protests that may prove surprisingly intense and broad.

This article was originally published at Carnegie Moscow Center