The liberalization of the gas sector in Ukraine is highly controversial due to the burden it places on Ukrainian households, who have historically relied on highly subsidized tariffs through price caps by the government. As a result of the ongoing reforms Ukrainian households faced a more than doubling in natural gas prices in the period 2013-2016, while their income has simultaneously declined with almost 50 percent. In his thesis Lisse van Vliet argues that instead of critically looking at the policies, Ukrainian institutions and international organizations blame the systemic corruption and the lack of understanding by the population for the problems in implementing reforms.

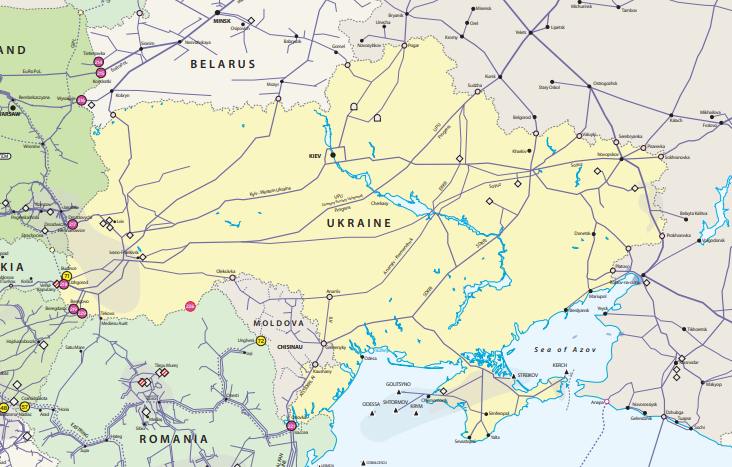

Gaspipes in Ukraine

Gaspipes in Ukraine

by Lisse Geert van Vliet

The Ukrainian gas sector reforms were initiated through its 2011 membership of the Energy Community, which obliged the Ukrainian government to comply with EU energy legislation. Following the adoption of a national Natural Gas Market Law in 2015, the necessary provisions for gas market liberalization were written into primary law. Subsequently gas tariff setting procedures were modified considerably, aiming to, inter alia, liberalize wholesale and retail gas prices. However, simultaneously a so-called Public Service Obligation (PSO) regime was introduced, which regulated the prices for the sale of gas to certain customer categories.

The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine was now allowed to assign PSO status to any gas company and starting October 1, 2015, the national gas company “Naftogaz” was assigned such status. As a result, Naftogaz was required to sell/supply gas at a regulated price to, first and foremost, regional supply and district heating companies. Furthermore, Naftogaz gained the right to receive compensation for all economically justifiable costs it incurred providing gas to households. Under the existing PSO regime, Naftogaz was not allowed to supply gas directly to households.[1]

Naftogaz was obliged to sells its domestically produced gas to designated regional gas retail companies (Oblgazzbuts), which are exclusively supplying gas to the households in a specific region of Ukraine. Naftogaz had no right to refuse selling gas, regardless of outstanding debt of these intermediaries.[2] As a result of this, the Ukrainian government still needed to fund losses incurred by the major gas company,[3] while collecting payments by Naftogaz from both Municipal Heating Enterprises (MHEs) and Distribution System Operators (DSOs) for gas supply was already highly problematic.

It should be clear that 70% of the DSOs are controlled by Regional Supply Companies (RSCs) or Oblgazes, with only a minimal stake for Naftogaz. In this way, RSCs have been able to maintain a monopoly in distributing gas to Ukraine’s regulated markets, acting as intermediaries purchasing gas from Naftogaz at below market price. This leaves ample room for vested interests and corruption schemes (among others selling gas to fictive consumers).[4] It is estimated that Naftogaz incurred losses related to the PSO amounted to a total of UAH 111 billion in the period 2015 to 2017, while it remained obliged to continue providing subsidized gas which in many cases was not paid or not paid within the agreed timeframe.[5]

Monetization of gas subsidies

The process of monetization of gas subsidies has been started in order to mitigate rising gas prices when former president Poroshenko was convinced to implement the process for political gains.[6] The monetized subsidy system envisions transfers directly into the bank accounts of vulnerable consumers, and should go into effect over three stages. Previously, these subsidies were given directly to the distributors of gas, a system highly prone to corruption, the new system envisions direct money transfers to citizens.

Coming from a system with eleven different subsidized prices for gas, the ongoing market liberalization in tandem with the reforms of the subsidy system hopes to relieve the Ukrainian government of the burden this places on their budget.[7] According to the neoliberal reforms, these subsidies need to be decoupled from the prices and monetization of subsidies based on real parameters needs to be implemented,[8] thereby incentivizing the recipient to economize.

However, reform proves difficult in this area, since during the first attempt to monetize housing and utility subsidies the obligation to operate the funds was shifted from the social security and treasury authorities to Multi Apartment Building co-owners association (MBCA) and service providers, which caused a public conflict and actual suspension of the reform for almost a year.[9]

Finally, full monetization was introduced in March 2019, which saw subsidies for gas being paid in cash.[10] Starting as a pilot project, currently two subsidy systems are in place: (1) new subsidy holders still receive in kind subsidies, which are subtracted from their gas bill; (2) subsidy recipients already part of the system before the introduction of monetized subsidies receive fully monetized subsidies since March 2019.

According to the DIXI Group, this dual system currently in place makes the subsidy system unnecessary difficult to understand.[11] Gas subsidies are now delivered to the recipient’s bank account in state-owned Oschadbank, or the local post office in case no such account exists, which is similar to the way in which pensions are handed out in Ukraine. In the quasi-monetization system Oschadbank pays the utility companies instead of the customer, after which the remaining part of the bill needs to be paid by the customer. Oschadbank bank has dedicated accounts to which suppliers send the subsidies.[12]

Unfortunately, the statistics for the effect of the first months of subsidy monetization were are still awaited at the time of writing,[13] with no data yet available, it is still unknown whether these subsidies have the desired effect of reducing the use of gas and protecting vulnerable customers.[14]

The anti-politics community

Essentially, all reforms currently under review in this MA thesis can be traced back to the implicit, blanket subsidies, covering all of the population, which are critiqued by the neoliberal reformers for the conception of pre-determined public value entailed in them.[15] This is joined by a portrayal of the Ukrainian gas market as suffering from both a lack of legislation and defects in existing legislation, which causes both political corruption and rent-seeking. This feeds the widespread belief that basically every part of Ukrainian society is influenced by this and that no actor in the gas sector is completely clean.[16]

With the official goal of the reforms being to further insulate the sector from undue political intervention and reduce corruption risk,[17] a continuing externalization of the burden for the lack of reform implementation has been taken place in the Anti-Politics Community in Ukraine.

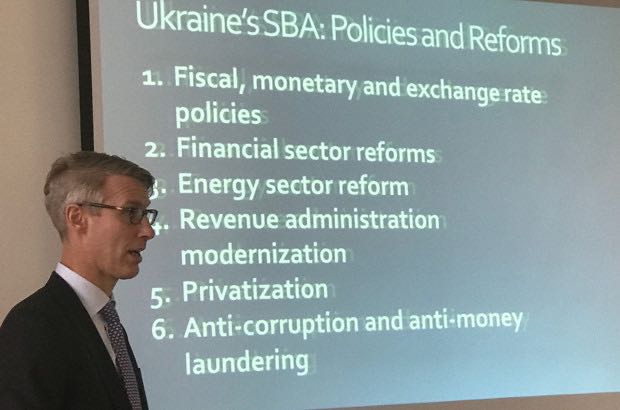

IMF representative in Ukraine lectures about reforms.Photo: imf.org

IMF representative in Ukraine lectures about reforms.Photo: imf.org

The general explanation provided by the ‘experts’ has been that for some reason people in Ukraine do not believe the provision of gas can stop and seem unaware of the urgency to pay for gas. This believe is then fueled by Ukrainian politicians who often claim that gas belongs to the people. As one Naftogaz representative explained: “By solely focusing on the rising prices they do not tell that Naftogaz pays 70% of its revenues to the state and the long term effect of subsidized prices. Gas prices are used as a political measure by Timoshenko and other parliamentarians”.[18] Concerning the monetization of subsidies, a recurring explanation is that it is: “difficult to convince a Babushka that monetization of gas subsidies and liberalization of gas prices are good for her and her country in the long run”.[19]

The argument goes that the Soviet legacy in Ukraine is the understanding that energy commodities are not something you would have to pay for in excess, since gas used to be cheaper than water. As one expert puts it: “For someone with a Soviet mindset, it is very difficult to change this way of thinking about gas, which puts a huge strain on the reforms”.[20] This myth of a ‘Soviet legacy’ administers all resistance in Ukraine to gas price liberalization and subsidy monetization to an apparent conflict between the neoliberalist and communist view on how “to govern a population’s health, welfare, and conditions of existence in the framework of political sovereignty”, referred to as Biopolitics.[21]

The neoliberal view is built on an understanding of individual empowerment and preference setting. This entails bringing gas prices to an import-parity level, which would greatly diminishes the incentives for gas-related rent-seeking, an increased level of metering and more transparency throughout the system.[22] However, the contrasting Soviet Social Modernity vision on governance understands “public value” as something to be determined by the state. The persistent legacy of the Soviet past would then be the expectation by citizens that the state provides for goods and makes an effort to provide for their lives in a material way.[23]

When the liberalization of gas price towards import parity level is problematized by Ukrainian politicians and companies, who make the claim that Ukrainian people should pay less for domestic gas than for imported gas, these arguments are being depoliticized by focusing on the incoherency with neoliberal theory. The reaction of the international community when the Ukrainian government left implicit gas subsidies in place, despite rising international prices, reference is made to the fact that it re-creates opportunities for corrupt schemes to divert household gas to industry and that it goes contrary to the ‘depoliticized’ obligations under the IMF agreement.[24]

Subsequently, the political influence by oligarchs, such as gas distribution companies owner Firtash, is time and again brought up as a danger to the ongoing reforms, as well as politicians campaigning against the gas price increases. During the 2019 presidential elections Tymoshenko, who most vocally opposed the liberalization by promising voters to cut back gas prices by 50%, was seen as real threat.[25]

Yulia Tymoshenko promised to cut back prices by 50%

Yulia Tymoshenko promised to cut back prices by 50%

This understanding of the impediments to the reforms has been extended to Naftogaz. According to them, the misunderstanding by Ukrainian of the reforms and the vested interests are most important impediments.[26] The fact that its representative completely follows the biopolitical thinking of the neoliberal reforms, becomes apparent from the following quote: “an interesting parallel can be drawn from a research on 1990’s Ukrainian political programs, which found that the main discussions then were revolving around the abolishment of subsidized prices for bread and what a negative impact this would have on society.

Notwithstanding, in contemporary Ukraine both are provided: subsidized bread for lesser well off consumers, and high class French bread for the people willing, and able, to pay more. Hopefully this will happen to the gas sector as well, with people paying a normal price for gas and vulnerable customers receiving subsidies”.[27]

It has been a common belief among reformers that a ‘change’ need to be brought about in the mentality of the Ukrainian citizens, in order for them to ‘understand’ the biopolitical system inherent to the neoliberal reforms, in combination with the extensive focus on corruption and vested interests, that create the prerequisite for a continued presence of international organizations and the externalization of the barriers to reform. This leads to a situation in which ‘development’ projects are solely judged by their own merits,[28] and little attention is paid to the social and ideological environment in which both the policy-making processes, and the broader politics of policy implementation and knowledge production take place.[29]

Conclusion

The most asked proverbial question in contemporary Ukraine is whether the glass is half full, or half empty. A general disbelief in the success of the reforms sharply contrast with the actual progress that has been made during Poroshenko’s presidency. These include Naftogaz reforms, an improved business model and the upsurge in attention among the international community for the implementation of these reforms.[30] In the end, it would be too simplistic to claim the gas market reforms simply “failed” or “succeeded”. While some goals were met, both negative and positive unforeseen consequences could be witnessed in the process.

This MA thesis argued that an anti-politics community has developed in Ukraine. Instead of looking critically at the policies being implemented, the lack of understanding about the gas sector reforms and the systemic corruption are given as a cause for the underperformance of the reforms.[31] It remains a question whether it is despite of, or because of, the many reforms implemented that Poroshenko lost the 2019 elections by almost a 50% difference in votes during the run-off round.[32]

No matter the effects and failures of development interventions, many scholars have noted that development is notable for creating: more development. This entails both the expansion of expertise, institutional presence and new projects to improve on failed ones.[33] This is certainly the case of Ukraine, with the government now investing a lot of efforts to promote the monetization of subsidies, and a general understanding among the ‘experts’ that the ‘biopolitical remnants of Soviet Social Modernity’, or mentality, gradually need to be phased out through more incremental changes.[34]

This master thesis can be read in full here

NOTES

[1] Naftogaz Group, 2018, p. 66.

[2] Naftogaz Group, 2018, p. 51.

[3] OECD, 2018a.

[4] Borosovskyi, 2017; Kharchenko, 2018; Konończuk and Matuszak, 2017.

[5] OECD, 2019, p. 54.

[6] Interview Naftogaz.

[7] Jarabik, Sasse, Shapovalova and De Waal, 2018.

[8] Interview DG ENER.

[9] DIXI Group et al, September 2018.

[10] Interview Naftogaz.

[11] Interview DIXI Group.

[12] Interview Naftogaz.

[13] Interview Naftogaz.

[14] Interview EEAS.

[15] Collier, 2011, p. 239.

[16] Interview DIXI Group.

[17] OECD, 2019, p. 12-13.

[18] Interview Naftogaz.

[19] Interview Support Group for Ukraine.

[20] Interview DIXI Group.

[21] Collier, 2011, p. 3.

[22] Rozwałka and Tordengren, 2016, p. 12.

[23] McMann, 2004.

[24] IMF, 2019, p. 16.

[25] Interview Support Group for Ukraine.

[26] Interview Naftogaz.

[27] Interview Naftogaz.

[28] Ferguson, 1994, p. 9-10.

[29] Hall, 1993; Robertson 1991.

[30] Interview Dutch MFA

[31] Interview DIXI Group.

[32] Interview Dutch MFA

[33] Kalinovsky, 2018, pp. 248-49.

[34] Interview DIXI Group.