The West is inclined to interpret and explain national politics by referring to Russia or Putin. However, the recent electoral misfortunes of mainstream liberalism and the rise of Euroscepticism have little to nothing to do with Putin, says international relations lecturer Camille Merlen. A direct effect of the West’s Russian obsession may paradoxically be an increase in Russian power. After all, power more often than not consists in the perception of power.

François Fillon’s unexpected landslide victory in the French primaries on the right once again highlighted the West’s obsession with Russia. The ex-Prime Minister, somewhat forgotten outside of France, is now considered the favourite to win the country’s 2017 presidential election. Whereas his vintage brand of social conservatism, his penchant for radical austerity policies, and his ambivalent stance on Europe have hardly been discussed, it was his allegedly pro-Russian inclinations that made the headlines all over Europe and the US, reflecting a trend of interpreting national politics through the prism of Russia.

Fillon and Putin during visit in Moscow, 2011. (Photo government.ru)

Fillon and Putin during visit in Moscow, 2011. (Photo government.ru)

To be sure, Fillon has never made a secret of valuing earnest cooperation with Russia. As Prime Minister under Nicolas Sarkozy, he was regularly in contact with Vladimir Putin, his Russian counterpart at the time, and the two developed a very cordial relationship. More recently, Fillon has denounced what he sees as an overly confrontational course vis-à-vis Moscow on behalf of the West, and criticised the sanctions taken against Russia in the wake of the incorporation of Crimea. In April, he and other members of his party even managed to adopt a parliamentary resolution calling for the lifting of European sanctions. A devout catholic, Fillon is also known to favour an alliance against ISIS with Putin and Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, notably in view of protecting Middle Eastern Christians.

Add to this Fillon’s harsh criticism of US foreign policy, and it is clear why commentators and political opponents have drawn the image of someone ready to appease Putin, whom many in the West have come to see as not just their main geopolitical opponent in the context of a ‘new Cold War’, but also as the personification of evil. As a consequence, Fillon was forced to distance himself from the Russian president after his win in the first round of the primaries. He explained that ‘Putin is not a friend but an interlocutor who respects those who are capable of keeping their engagements’, while he called Russia ‘a dangerous country because it is loaded with nuclear weapons, and has never known democracy’.

Nonetheless, Fillon’s win in the primaries was widely characterised as another victory for Putin in his attempts to divide the West and increase his influence in Europe. This is all the more the case since Fillon’s opponent in the second round is likely to be the Front National’s Marine Le Pen: as she is seen as even more pro-Russian than Fillon, this would supposedly be a win-win-situation for Moscow.

'Useful idiots'

The episode highlights a mechanism that has become quite familiar over the course of this year. It consists in suggesting a certain connivance with Russia, and in particular its president, in the hope that some of the wickedness of the latter will give off on your target. It also reflects an obsession sometimes bordering on paranoia that consists in interpreting and explaining national politics by referring to Russia or Putin, the two being virtual synonyms in today’s media parlance.

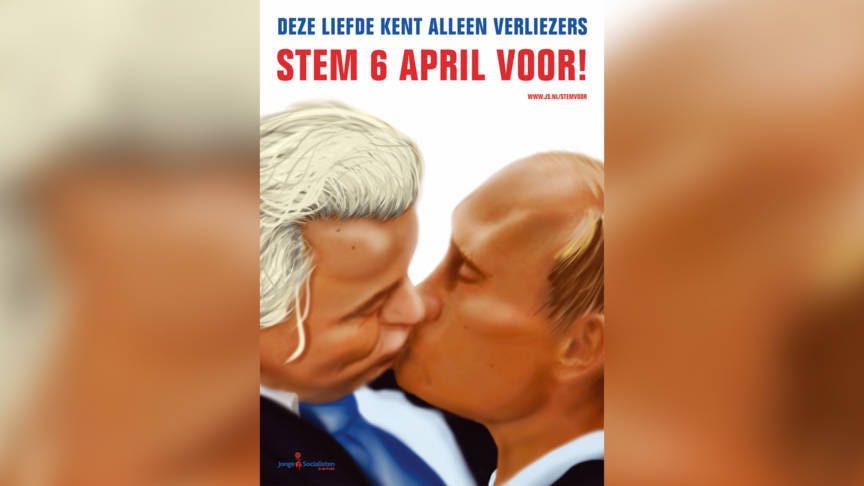

Campaignflyer Dutch Young Socialists

Campaignflyer Dutch Young Socialists

For instance, in the run-up to the Dutch referendum on the Association Agreement with Ukraine in April, ‘no’-voters were widely castigated as ‘useful idiots’ serving the master of the Kremlin. Likewise, the ‘Remain’-campaign claimed that Russia was backing the ‘Leave’-campaign in the UK, with David Cameron stating that Putin ‘might be happy’ if the UK left the EU. Most notoriously, the US presidential campaign was dominated by recurrent accusations of serious Russian interference in favour of Donald Trump. It will only be a matter of time before we see similar allegations concerning the French elections, as well as the Dutch and perhaps German ones in 2017.

In the most direct sense, this tactic has proven wholly ineffective: in the end, the Dutch still voted against the Association Agreement, the British for Brexit, and the Americans for Trump — thereby, supposedly, all but increasing the Kremlin’s influence in the West. Accordingly, the outcome of these elections have only further fed paranoia over Russian covert operations, ‘fake news’, and other machinations threatening Western democracies. Indeed, simply being a Eurosceptic — let alone professing a willingness to work with Russia or wanting to do business with it — is nowadays enough to be considered a part of the ‘new Putin coalition’. Reflecting this wide-held sense of impending danger, the New York Times thus discerns a ‘tectonic shift [...] toward accommodating, rather than countering, a resurgent Russia’.

Intellectual poverty

What this points to is more worrisome than the casual Russophobia that pervades the public debate. The interpretation of domestic politics by Western politicians and journalists through the prism of Russia obscures what is actually behind some of the political shifts that we are witnessing today. Indeed, the recent electoral misfortunes of mainstream liberalism and the rise of Euroscepticism have little to nothing to do with Putin, and everything with the manifold perceived failures of the current political class — including a rise in feelings of cultural insecurity, a widening wealth gap, and a hollowing out of democracy — itself seen as unable or unwilling to put a change to any of them.

Moreover, glossing over the specifics of each national context seems like a sign of significant intellectual poverty when it is precisely the dynamics of domestic politics that remain determining. Britain, for instance, has always entertained a highly ambiguous relationship with the European Union. Likewise, the tragedy of Trump is that he is 'a thoroughly American creation’ rather than some kind of foreign agent. What is needed, therefore, is an acknowledgement that these issues are homegrown: ignoring them by directing attention towards imaginary Kremlin master plans will not solve them.

Fillon’s position on Russia is first and foremost informed by a Gaullist tradition — to which inter alia all but the last two French presidents of the 5th Republic have adhered — that is critical of US leadership, treasures French independence in international affairs, and accordingly seeks to strike a balance between its different geopolitical partners. There seems little irrational in such an approach and if anything, the current crisis with Russia and the situation in the Middle East demonstrate precisely the dangers of a blind overreliance on the US and neglecting the interests of others.

Marine le Pen and Nigel Farage in front of a picture of Joan of Arc, May 2014 (photo Tjebbe van Tijen)

Marine le Pen and Nigel Farage in front of a picture of Joan of Arc, May 2014 (photo Tjebbe van Tijen)

Blaming the enemy for one's own faults

Two final ironies are worth pointing out. The first concerns the fact that blaming society’s ills on evil outside forces is, of course, precisely one of the West’s own favourite criticisms of Russia. That many in the West now choose to do the same only lends credence to Russia’s claim of moral equivalence. It is highly telling that the EU Parliament’s recent resolution condemning Russian propaganda, ‘fake news’, and disinformation (and equating it with ISIS’ efforts) was proposed by a member of the Polish ruling party Law and Justice, currently engaged in an assault on media pluralism at home.

Second, one of the direct effects of the West’s Russian obsession may paradoxically be an increase in Russian power. After all, power more often than not consists in the perception of power. When serious commentators therefore caricature Russia’s capabilities (deciding on the next US president or a country’s EU membership, for instance) they are therefore helping that situation to materialise, as others may begin to believe that this is the reality they are living in and will start acting accordingly. The ultimate danger here is that even the Russian leadership may accept this narrative as true and will feel emboldened to embark on ever more reckless behaviour.