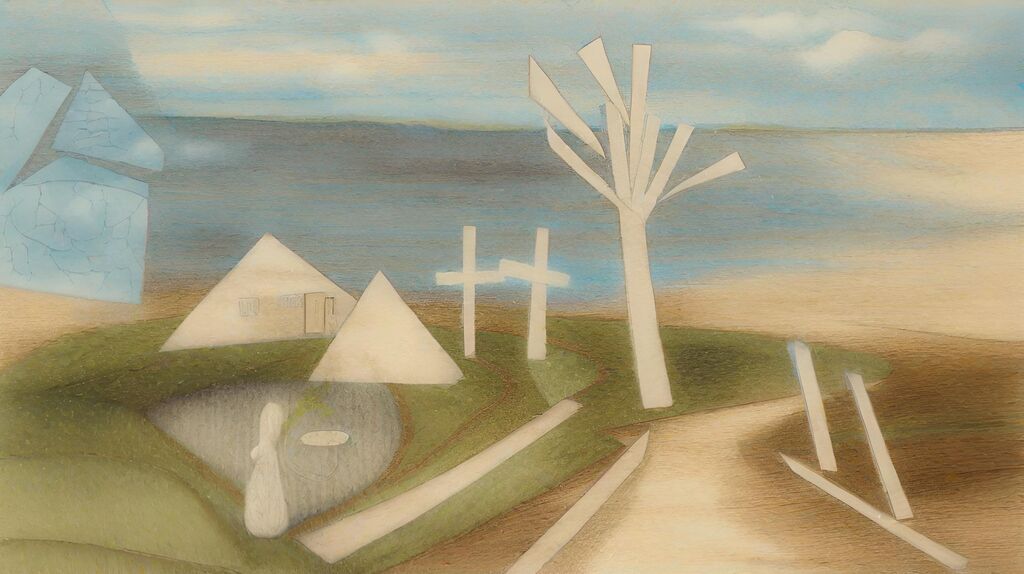

This week, we introduce our new name: RAAM, a window on Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. An important reason for this name change is our belief that Russia, Ukraine and Belarus deserve an equal place on the platform. We are therefore glad to be able to mark this moment with a special contribution from a young artist from Belarus, the most underexposed country of the three. Whereas Belarus largely disappeared from the news, political repression following the fraudulent presidential elections of 2020 continues unabated. In her essay, the artist reflects on her youth in the Belarusian countryside, on her current position as an artist abroad, and on learning to feel fear. For the sake of safety, we publish the essay in an anonymised form.

At a meeting with extremists

I’m sitting at a round table, at a closed meeting with Belarusian opposition leaders. The host reminds us that if there are any KGB-agents in the room, she will have to disappoint them: we won’t share useful information or discuss extremist material.

Some time ago I would probably have laughed when someone mentioned the KGB. For me, all those stories about spies were more like myths from a far away past. Now, living in the Netherlands and following the news about my home country, I learn that the Belarusian government allocates extra funding for spying on activists’ activities abroad. Anything the government considers ‘a danger to the vitality of the regime,’ is called ‘extremist’.

When I grew up, to me the term ‘extremist’ was equal to something horrible, equal to terror. I always had good marks at school and considered myself a ‘good person,’ ‘a good citizen’ even. The fact that I’m now regularly present at meetings with respectable people, many of whom are called 'extremists' and 'terrorists' by the Belarusian regime, is something that I still find hard to understand.

To be unable or afraid to visit your home is a strong punishment

I can’t discuss any of my activist work with my parents, because for them it’s a danger zone they would rather avoid. They’re worried about me. We had many arguments, then started to avoid certain themes. We don’t discuss politics, we don’t discuss the war in Ukraine. I try to distance myself from the thought that my parents might defend the regime and the system that has done so many awful things to so many people. I find it difficult to accept that they might be afraid, too. Instead, we talk about the harvest in August, we talk about flowers in spring, about little news from our relatives and friends. Everything but politics. Only when it’s about me visiting home, we agree that it’s too dangerous for me. We don’t speak about why exactly this is the case. The reasons are kept off the kitchen table.

I still care about my roots. I miss my hometown, I miss the river where I used to swim as a child, I miss sitting at my grandpa's grave on the hill, where it’s always windy. I had very tough years, especially since the invasion of Ukraine. Just before 24 February 2022, I was planning to visit my second grandma, I felt there wasn’t much time left. She passed away in March of that year, and I couldn’t say goodbye. She never found out about the war in Ukraine. I think she would’ve gotten very angry about the stupidity of people. Because she lived through the second world war in occupied Belarus, and I cannot imagine that anyone who lived through war can support this horror again.

To be unable or afraid to visit your home is a strong punishment. No matter the regime, we carry our dear connections and friendships in our heart, we have places where we used to hide.

I’m sad and out of tune,

My teacher told me once:

You better leave this swamp.

Big city lights invited,

along with golden island shores.

Time passed, I forgot my swamp.

I enter an old apartment block,

For the first time since my youth.

Big windows, floral wallpaper,

furniture that once was new.

From my former bedroom,

I stare at a familiar view.

My youth bloomed yesterday,

Now someone’s starting anew.

I hear children laughing,

In my empty room.

Old memories running through my veins,

And I’m feeling blue.

I'm standing on my soil,

begging for forgiveness.

Here I’ve lived, and even loved,

So much time has passed.

I find our summer house,

And hug the tree we climbed.

I find my way to the path,

to where I used to hide.

I love this messy route,

My steps in the swamp,

Where the earth seems to gurgle.

The moon is shining,

To show the way.

One day, I’m coming back.

I hope my land accepts my prayer.

I miss Belarusian nature, its deep forests and blue lakes. I wish I was able to visit my family whenever I want. I need it. But unfortunately, it seems a luxury. Things could be worse. I follow the daily news and understand how deeply inhuman the Belarusian regime is, and there’s no one to complain.

We went through a time of despair and disbelief

Belarus disappeared from the news a long time ago. I think that many Belarusians would agree when I say that in the years following the anti-government protests of 2020, we went through a time of despair and disbelief. Many people suffered, lives were damaged, scattered, our beliefs and hopes were damaged. Many activists I knew crashed. We almost lost our hope.

But - I’ve been there - this is not a solution. Without hope, there is no light. Now I see that some activists slowly start to come back. It’s not so much an outer fight, but an inner one: a need, a belief in the importance of our own small actions.

When I joined the protests in 2020, I had little information about the Belarusian regime, its tools and its power. I openly expressed my opinion on social media, spoke to western newspapers, organized talks and discussions. We were convinced that soon the regime would fall. Now, knowing what happened, I’m no longer ashamed to be afraid. The recent imprisonment of the members of the musical group Tor Band (7.5 to 9 years) confirms that the regime sees artists as a threat. With my actions, I could put myself or my parents at risk. I don’t give up, but I have to change the way I operate. I am learning to feel my fear.

We need to get rid of the dictators within ourselves

The challenge of anyone born in a dictatorship is to learn to respect your own rights, to embrace different opinions, and to believe in change. We need to get rid of the dictators within ourselves. Of course, many things depend on your family. If you’re from a place where sharing personal opinions mattered, and personal choices were respected, it becomes easier to deal with suppression. Unfortunately, our parents used to protect us by limiting our choice. And now it’s hard to build a democracy, without the experience of listening to yourself and your own needs. As an adult, I first of all had to learn to be free inside myself.

I never had a grandfather or grandmother who would openly talk with me about politics, who would express frankly what was happening. Maybe I was too young then, or maybe they have been through so much so they hardly talked about it. Now I see much older people in the opposition, people who have seen more than me. Just like me, they once left Belarus because of their beliefs. Some were forced to flee. Here at the table one man admits: 'I’m 72 years old, and I’m forced to live in immigration. Yes, It’s difficult, one has to start a new life from scratch. But since we’re here in Europe, albeit forced, we can use this time to study the institutions of democracy. We must know the mechanics of the dictatorships that we want to resist. I’ve lived under communism, when we waited for the regime to fall. But instead of waiting, we must actively prepare for this fall. We must know what we’re up against, and not waste our precious time.'

The meeting made me feel safe and gave me hope

The meeting made me feel safe and gave me hope. I really believe in the power of people, and I believe in justice. It may take a very long time for Belarus to come to terms with all that has happened. It may need an absolutely new system, a new constitution, new regulations that would never allow one person to gain so much power. Much work needs to be done: history has to be cleaned from propaganda. All victims of the Belarusian regime and its predecessor need to be recognized. But I believe in these people, I believe in myself, and in our joint future.